Yvana I. When you open up, the burden doesn’t feel so heavy.

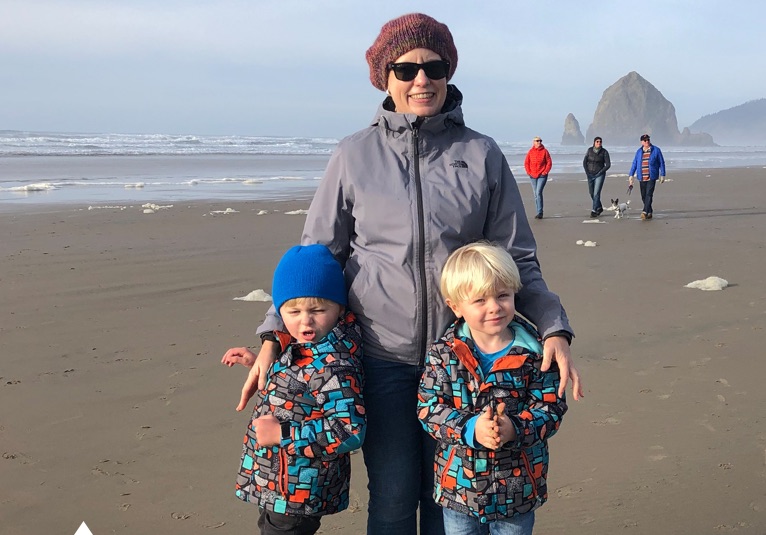

Meet Yvana.

I grew up in Brooklyn, New York, immigrant family, and always felt like I wanted to help the poor. And so I went to medical school and in residency, I spent six years on the Navajo reservation, then spent the past 25 years with the Mexican farmworkers’ clinic in Toppenish.

When Covid hit, I have bad asthma, and I had a really bad asthmatic attack. I was put on all these meds and so I took medical leave. At the end of the medical leave, I thought, I can’t go back. I need to resolve my health issues.

That part was probably the worst for me. Deciding to leave my job was so fraught with incredible, incredible guilt because my colleagues were still there, the nurses were still there. But it was more just the guilt of leaving this medical family.

I always felt that mental health is super important. And I also feel that society doesn’t treat it correctly. I just think our medical system needs such a revamp. When they talk about people debating, “Should I pay my money for my rent or my medicine?”, people are also debating, “Should I pay my money to see someone? So do I talk to someone and pay money that way or do I pay money for food and rent?”

That’s what’s so incredibly sad. That’s what hurts the most – thinking about people who probably need to see someone who can’t, who can’t afford it, who don’t have the time because they have to work so they can make money so they have health insurance.

I think that’s going to be an epidemic of mental health problems for health care workers. I think that’s going to be huge because I think we’re like the pitcher. We give and we give and we give and nobody fills us back up.

It’s like a breath of fresh air when you do share it. It’s like there’s other people who feel like that, just like me. And now the burden doesn’t fell as heavy.

But I felt like I could concentrate on getting my health back in order, I could concentrate on my family.

We’re all human. No matter what our religion, political leanings, whatever there is, there’s a core of humanity in all of us.

I always got a lot of support from my woman friends, and I relied on them even more. We would text each other every day: how are you doing? How are things going? I think it made the bonds super close.

I live in a little housing community, really tiny, and it was built to have like neighbors and people on porches. We couldn’t go over each other’s houses, but we were able to stand outside and talk to each other. And that was incredible. It brought us all closer.

I think we had blindfolds on.

We were just going through life, and [the pandemic] put a halt to everything and made us take a step back. It was a time of reassessment of our lives, of what’s happening.

I think sometimes we forget. We always look at someone else and say, “oh, they have it so much better,” or, “I wish I could be that person because they’re not dealing with this.” That’s not true. And the only way we know that’s not true is if you share by interacting with other humans. When you do, it’s like a breath of fresh air. It’s like, oh, there’s other people who feel like that, just like me. Now the burden doesn’t feel as heavy.

That sense of giving, of taking care of someone else pulls you out of yourself. I think it’s sweet now; people are more willing to talk, because I think people are lonely. When you meet people who normally wouldn’t stop and say anything, they talk to each other because we haven’t in so long.